Cross-posted from The Neuroethics Blog (Emory University Center for Ethics)

A number of potentially problematic themes run throughout public discussions about sexuality in this country. One such potentially problematic theme revolves around innate sex/gender differences in sexuality. I see stories in the media almost every week about how men and women are almost diametric opposites when it comes to sexuality as a result of evolutionary pressures. In these articles, which are often reporting on scientific studies, the men are invariably sex-hungry and desperate to procreate with any available woman, while the women are invariably choosy and determined to find a “good provider” (for examples, see here, here, and here). I suspect these articles (and the studies they draw from) suffer from confirmation bias, developing elaborate evolutionary rationales to justify what seem like outdated stereotypes.

A number of potentially problematic themes run throughout public discussions about sexuality in this country. One such potentially problematic theme revolves around innate sex/gender differences in sexuality. I see stories in the media almost every week about how men and women are almost diametric opposites when it comes to sexuality as a result of evolutionary pressures. In these articles, which are often reporting on scientific studies, the men are invariably sex-hungry and desperate to procreate with any available woman, while the women are invariably choosy and determined to find a “good provider” (for examples, see here, here, and here). I suspect these articles (and the studies they draw from) suffer from confirmation bias, developing elaborate evolutionary rationales to justify what seem like outdated stereotypes.

Another such theme revolves around the determinative role of hormones in sexual desire and activity. In a fascinating (although now somewhat out-of-date) study, sociologist Amy Schalet interviewed parents in the U.S. and the Netherlands about adolescent sexuality. She found that American parents were much more likely than Dutch parents to view adolescent sexuality as driven by hormones. In addition (perhaps as a result) American parents, unlike Dutch parents, viewed adolescent desire as potentially dangerous, and they were more likely to adopt an attitude of willful ignorance about the sexual activity engaged in by their children.

Frontiers in Neuroscience talk: “Response to Sexual Images: Neural Activation and Hormonal Influences”

A recent talk I attended reconfirmed my belief that both of these views (about hormones and about innate sex/gender differences in sexuality) are, at best, overly simplistic. The talk, titled “Response to Sexual Images: Neural Activation and Hormonal Influences” was by Dr. Kim Wallen, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Neuroendocrinology at Emory University. Dr. Wallen is an international leader in the study of hormonal influences on the sexual behavior of rhesus monkeys. About a decade ago, he turned his attention to humans, and since then he has been involved in a series of studies investigating the connection between hormones and gender differences in sexual functioning in humans (Hamann et al 2004; Rupp and Wallen 2007; Wallen and Rupp 2010; some studies not yet published). I had the pleasure of sitting in on one of Dr. Wallen’s undergraduate courses, the Behavioral Neuroendocrinology of Sex, last year, and I was constantly impressed by the careful attention he paid to the confluence of social and biological influences on sexual behavior.

A recent talk I attended reconfirmed my belief that both of these views (about hormones and about innate sex/gender differences in sexuality) are, at best, overly simplistic. The talk, titled “Response to Sexual Images: Neural Activation and Hormonal Influences” was by Dr. Kim Wallen, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Neuroendocrinology at Emory University. Dr. Wallen is an international leader in the study of hormonal influences on the sexual behavior of rhesus monkeys. About a decade ago, he turned his attention to humans, and since then he has been involved in a series of studies investigating the connection between hormones and gender differences in sexual functioning in humans (Hamann et al 2004; Rupp and Wallen 2007; Wallen and Rupp 2010; some studies not yet published). I had the pleasure of sitting in on one of Dr. Wallen’s undergraduate courses, the Behavioral Neuroendocrinology of Sex, last year, and I was constantly impressed by the careful attention he paid to the confluence of social and biological influences on sexual behavior.

While listening to his talk, I was struck by two things. First, I was struck by the “messiness” of the data and the difficulty I had in drawing meaningful conclusions from the different studies. Second, I was struck by what the studies do seem to reveal: There are certainly both hormonal influences on sexuality and sex/gender differences in sexuality. However, the relationship between hormones and sexuality is extremely complex. In addition, sex/gender differences in sexuality sometimes run counter to common stereotypes and these differences are clearly neither innate nor learned but are produced through an ongoing intra-action of biological and social factors. If you will bear with me, I would like to undertake a somewhat detailed review of the studies Dr. Wallen discussed in his talk in order to illustrate these points.

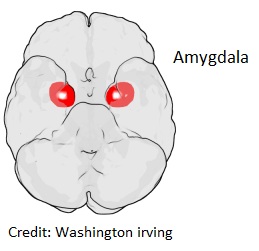

Study I: Differences between heterosexual women and men in neural activation when viewing erotic stimuli

In the first study (Hamann et al 2004), the investigators sought to determine whether there are differences in neural activation between young heterosexual men and women when viewing erotic stimuli, even when they report similarly high levels of subjective sexual arousal in response to the stimuli. The study found that neural activation was largely similar in young men and women in response to erotic images. However, even though the men and women reported similar levels of arousal, the men showed greater neural activation in the amygdala and the hypothalamus than the women.

In the first study (Hamann et al 2004), the investigators sought to determine whether there are differences in neural activation between young heterosexual men and women when viewing erotic stimuli, even when they report similarly high levels of subjective sexual arousal in response to the stimuli. The study found that neural activation was largely similar in young men and women in response to erotic images. However, even though the men and women reported similar levels of arousal, the men showed greater neural activation in the amygdala and the hypothalamus than the women.

I am impressed by this study for a number of reasons, including the care the investigators took to select images that the women would find arousing, their focus on gender similarities as well as differences, and their insistence that no claims about causality (i.e., that the differences are the result of socialization or hormones) can be made on the basis of the data. However, what struck me in reading the study was the difficulty I had in drawing meaningful conclusions from the data. Part of the problem comes from the fact that the investigators used four sets of stimuli (erotic couples, opposite sex nudes, non-erotic couples, and a fixation baseline), and the results are widely divergent depending on what you compare to what. For example, the women showed activation in the left amygdala when comparing the opposite sex nudes to the fixation baseline, but not when comparing the erotic-couples or the non-erotic couples to the fixation baseline. What could this activation in response to the opposite sex nudes mean? And, as Canli and Gabrieli point out, the women in this study did not show any greater relative activation in the amygdala or the hypothalamus for the erotic-couples stimuli compared to the non-erotic couples stimuli, even though they reported finding the erotic couples more arousing. As Canli and Gabrieli state, “It is unclear, therefore, which neural system mediates the sexual arousal reported by the women in this study.” In addition, we still know so little about the functions of the left and right amygdala (or, to be more precise, we know that the amygdala is involved in so many different things, including emotional arousal and appetitive incentive motivation) that it is difficult to say what it means that the male subjects showed greater activation in this area in response to sexual stimuli.

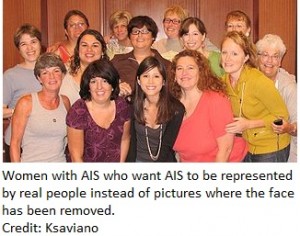

Study II: Differences in neural activation in women with androgen insensitivity syndrome

In the second study (which has not yet been published), the team looked at differences in neural activation between heterosexual men, heterosexual control women, and (presumably) heterosexual women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) when viewing sexual stimuli. According to Dr. Wallen, the control women and the women with CAIS did not differ in amygdala activation. The men differed from both the control women and the women with CAIS in amygdala activation, and, in fact, the difference between men and women with CAIS was greater than the difference between men and control women. According to Dr. Wallen, although cultural influences cannot be ruled out, the results “suggest a role for prenatal androgen exposure in determining neural activation to sexual stimuli.” Yet, using observations of adults who were exposed to unusual levels of hormones in utero to draw conclusions about the role of prenatal hormones in determining behavior can be difficult. In a recent article, Rebecca Jordan-Young and Raffaella I. Rumiati critique the conclusions that have been drawn based on studies of women with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Women with CAH and women with CAIS have very different conditions. However, studies of women with CAIS may suffer from similar problems as studies of women with CAH: women with CAIS may be subject to greater than average levels of medical intervention; they may experience sex differently because they do not have a uterus or ovaries (thus they are infertile and do not menstruate); they may behave differently as a result of knowing their own CAIS condition; they may be treated differently by others who have knowledge of their CAIS condition; and/or they may be treated differently by others as a result of subtle physical characteristics (i.e. women with CAIS often look very “feminine”). Any of these factors could produce differences in the sexuality of women with CAIS.

In the second study (which has not yet been published), the team looked at differences in neural activation between heterosexual men, heterosexual control women, and (presumably) heterosexual women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) when viewing sexual stimuli. According to Dr. Wallen, the control women and the women with CAIS did not differ in amygdala activation. The men differed from both the control women and the women with CAIS in amygdala activation, and, in fact, the difference between men and women with CAIS was greater than the difference between men and control women. According to Dr. Wallen, although cultural influences cannot be ruled out, the results “suggest a role for prenatal androgen exposure in determining neural activation to sexual stimuli.” Yet, using observations of adults who were exposed to unusual levels of hormones in utero to draw conclusions about the role of prenatal hormones in determining behavior can be difficult. In a recent article, Rebecca Jordan-Young and Raffaella I. Rumiati critique the conclusions that have been drawn based on studies of women with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Women with CAH and women with CAIS have very different conditions. However, studies of women with CAIS may suffer from similar problems as studies of women with CAH: women with CAIS may be subject to greater than average levels of medical intervention; they may experience sex differently because they do not have a uterus or ovaries (thus they are infertile and do not menstruate); they may behave differently as a result of knowing their own CAIS condition; they may be treated differently by others who have knowledge of their CAIS condition; and/or they may be treated differently by others as a result of subtle physical characteristics (i.e. women with CAIS often look very “feminine”). Any of these factors could produce differences in the sexuality of women with CAIS.

Study III: What do women and men look for in erotic images?

![]() In the third study, Dr. Wallen and Heather Rupp set out to test whether men and women are looking at the same thing when they look at erotic images. In order to test this, they tracked the eye movements of heterosexual men and women (half of the women were using hormonal contraceptives) while they looked at erotic images of heterosexual couples on three different occasions (Rupp and Wallen 2007; Wallen and Rupp 2010). Overall looking patterns were similar. However, to their surprise, the men on average spent more time than the women looking at female faces. The “non-contracepting” women spent more time on average looking at genitals than either the men or the “contracepting” women. The contracepting women spent more time looking at “contextual” regions of the pictures (clothing or background) than the other two groups. All three groups spent about the same amount of time looking at female bodies (not counting the genitals). None of the groups spent as much time looking at male faces or male bodies (not counting the genitals), although the men spent the least amount of time of any group looking at male faces and bodies. Rupp and Wallen conclude that men and women don’t necessarily look at erotic images the same way (which perhaps leads to the observed differences in neural activation patterns), and that taking hormonal contraceptives influences how women look at erotic images. Again, however, I found it difficult to make meaning out of these results: why, for instance, does no one seem particularly interested in male faces or male bodies, apart from their genitals? Why did the men spend more time looking at female faces? Why did everyone spend the same amount of time looking at female bodies? Dr. Wallen has offered some thoughts about why this might be the case, but his explanations are speculative.

In the third study, Dr. Wallen and Heather Rupp set out to test whether men and women are looking at the same thing when they look at erotic images. In order to test this, they tracked the eye movements of heterosexual men and women (half of the women were using hormonal contraceptives) while they looked at erotic images of heterosexual couples on three different occasions (Rupp and Wallen 2007; Wallen and Rupp 2010). Overall looking patterns were similar. However, to their surprise, the men on average spent more time than the women looking at female faces. The “non-contracepting” women spent more time on average looking at genitals than either the men or the “contracepting” women. The contracepting women spent more time looking at “contextual” regions of the pictures (clothing or background) than the other two groups. All three groups spent about the same amount of time looking at female bodies (not counting the genitals). None of the groups spent as much time looking at male faces or male bodies (not counting the genitals), although the men spent the least amount of time of any group looking at male faces and bodies. Rupp and Wallen conclude that men and women don’t necessarily look at erotic images the same way (which perhaps leads to the observed differences in neural activation patterns), and that taking hormonal contraceptives influences how women look at erotic images. Again, however, I found it difficult to make meaning out of these results: why, for instance, does no one seem particularly interested in male faces or male bodies, apart from their genitals? Why did the men spend more time looking at female faces? Why did everyone spend the same amount of time looking at female bodies? Dr. Wallen has offered some thoughts about why this might be the case, but his explanations are speculative.

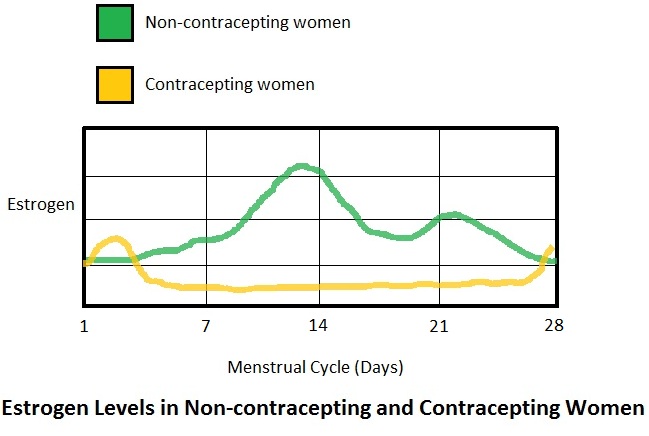

Wallen and Rupp further analyzed the data obtained from the women in order to assess the relationship between the phase the woman was at in her menstrual cycle and the time she spent looking at erotic images (Wallen and Rupp 2010). They found that the average time a woman spent looking at the images during the first test depended on what phase she was at in her menstrual cycle: the women at the stage in their cycle with the highest relative levels of endogenous estrogen (during menstruation for contracepting women and during ovulation for non-contracepting women) spent the longest time looking at the images. In addition, the women who spent the longest amount of time looking at the images during the first test also spent the longest amount of time looking at the images during the second and third tests. According to Wallen and Rupp, greater looking time reflects greater sexual interest. This suggests that a woman’s level of interest in erotic images may be related to her hormonal state during the first test. Yet, this study also suggests that the relationship between hormonal levels and interest in erotic images is a complex one. Interest in erotic images wasn’t related to absolute levels of circulating estrogen: interest was related to hormone levels at initial cycle phase only, and the group of contracepting women with the longest looking time (those who were menstruating during the first test) actually spent more time looking at the images than the group of non-contracepting women with the longest looking time (those who were ovulating during the first test), but it is unlikely that the contracepting women had higher absolute levels of estrogen during menstruation than the non-contracepting women had during ovulation (and how does any of this relate to the finding that contracepting and non-contracepting women look at erotic images differently?). In addition, the authors also found that women’s viewing times and subjective ratings were significantly correlated with their previous viewing experience, which suggests that social factors (including access to erotic images, stigma attached to women viewing erotic images, etc.) can have a significant influence on women’s interest in viewing erotic images.

Wallen and Rupp further analyzed the data obtained from the women in order to assess the relationship between the phase the woman was at in her menstrual cycle and the time she spent looking at erotic images (Wallen and Rupp 2010). They found that the average time a woman spent looking at the images during the first test depended on what phase she was at in her menstrual cycle: the women at the stage in their cycle with the highest relative levels of endogenous estrogen (during menstruation for contracepting women and during ovulation for non-contracepting women) spent the longest time looking at the images. In addition, the women who spent the longest amount of time looking at the images during the first test also spent the longest amount of time looking at the images during the second and third tests. According to Wallen and Rupp, greater looking time reflects greater sexual interest. This suggests that a woman’s level of interest in erotic images may be related to her hormonal state during the first test. Yet, this study also suggests that the relationship between hormonal levels and interest in erotic images is a complex one. Interest in erotic images wasn’t related to absolute levels of circulating estrogen: interest was related to hormone levels at initial cycle phase only, and the group of contracepting women with the longest looking time (those who were menstruating during the first test) actually spent more time looking at the images than the group of non-contracepting women with the longest looking time (those who were ovulating during the first test), but it is unlikely that the contracepting women had higher absolute levels of estrogen during menstruation than the non-contracepting women had during ovulation (and how does any of this relate to the finding that contracepting and non-contracepting women look at erotic images differently?). In addition, the authors also found that women’s viewing times and subjective ratings were significantly correlated with their previous viewing experience, which suggests that social factors (including access to erotic images, stigma attached to women viewing erotic images, etc.) can have a significant influence on women’s interest in viewing erotic images.

Take home message?

What lessons, if any, can be drawn from this slog through the data? I think this analysis shows that when your studies are designed by a careful researcher who is attentive to the interplay between social and biological influences on sexual behavior, you don’t end up with results that are easy to boil down into catchy sounds bites about the determinative role of hormones or the innateness of sex differences in sexuality. Instead, you end up with results that present a complicated, and sometimes difficult to interpret, picture about the relationship between hormones, sex/gender, mind/brain, and sexuality.