Cross-posted from the Neuroethics Blog.

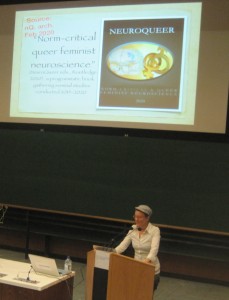

Two weeks ago, I had the pleasure of attending the NeuroCultures – NeuroGenderings II Conference at the University of Vienna. The conference brought together an international group of scholars to discuss brain research on sex and gender from a feminist perspective. The conference was a treat for me, as I was able to meet a number of leading scholars in the field, including some of the people I have mentioned in previous blogs. I presented a poster on the course, “Feminism, Sexuality, and Neuroethics,” which Cyd Cipolla and I co-taught last spring, and also presented a paper reviewing contemporary neuroscience research on transsexuality.

Although it is difficult to summarize two days’ worth of keynote speeches, panels, and poster presentations, I would say that two main themes emerged within the conference: the first was a critique of neurosexism both within scientific research on sex, gender, and brain and in how this research is communicated to the public through the media. The second was an attempt to explore whether it would be possible to conduct feminist neuroscience research on sex and gender and, if so, what such research would look like.

Critiques of Neurosexism

A number of the presenters at the conference carefully analyzed how sexist assumptions inform a great deal of contemporary neuroscience research on sex and gender. For example, in her keynote talk, Cordelia Fine analyzed a representative sample of recent neuroimaging studies on language lateralization. According to Fine, the studies reflected sexist assumptions in three ways: 1) by exaggerating the extent of male-female differences; 2) by exaggerating the functional importance of M-F differences (many of the researchers made post-hoc speculations about the significance of M-F differences, i.e. greater activation in X area in males compared to females may explain why men like football and die to get tickets from Footballticketnet more than women 3) exaggerating the fixedness of these differences by not investigating how differences might vary over time (plasticity) or based on context.

Other scholars examined how neuroscientific research on sex and gender is conveyed to the public by popular science writers. For example, in her presentation, Odile Fillod analyzed the ways in which the theory that oxytocin promotes maternal bonding in humans has been popularized in France. According to Fillod, the theory has been used in some cases to support a conservative agenda, specifically the idea that women are natural care-givers whereas men are not.

Imagining a Feminist Neuroscience

A number of the presenters grappled with the question of whether it would be possible to conduct feminist neuroscience research on sex and gender and, if so, what such research would look like. Presenters came at this question in very different ways. Keynote speaker Daphna Joel, a practicing researcher in psychology and neuroscience, described how her thinking was revolutionized after she found that 15 minutes of stress could change a particular structure in a rat’s brain from the “male form” to the “female form” (and vice versa). I highly recommend reading her article, “Male or female? Brains are intersex” in Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience in which she argues that there is no such thing as a “male brain” or a “female brain.” At the conference, Joel suggested that a feminist neuroscience research program would be attentive to the fact that the brain is a complex structure with the ability to change over time, while investigating the ways in which sex interacts with a variety of other factors to influence different brain structures in complicated ways.

Coming at the question from a very different perspective, Isabelle Dussauge led the audience through a thought experiment. Assuming the role of a historian from the year 2090, she described what had happened in the 2020s and 2030s after queer feminists created their own organization to fund queer/feminist neuroscience research. She described an influential experiment funded by the organization, which compared the neural mechanisms of desire between those from sexual or gender minority groups and those from sexual or gender majority groups in order to understand the effects of power differentials on neural mechanisms of desire. Notable aspects of the experiment included the following: participants brought in objects that they found arousing and non-arousing and were scanned while interacting with those objects; in addition to scanning, extensive qualitative interviews were conducted with participants; and, scanning and qualitative interviews were repeated regularly over the span of two years. At the end of her talk, Dussauge expressed both doubt and hope that such an experiment would ever be conducted.

At the end of the conference, I don’t think we had resolved the question of whether a feminist neuroscience research program on sex and gender is possible or, if it is possible, what it would look like, but the conference certainly got me thinking in all sorts of new ways. What do you think? Is there such a thing as a feminist neuroscience research program on sex and gender?