Cross-posted with permission from the Neuroethics Blog.

In this post, I would like to highlight the work of another Emory graduate student, Sara Freeman. Just when Cyd Cipolla and I (in the Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies) were coming up with our plan to teach an interdisciplinary course bringing together gender studies and neuroscience, we found out that Sara (in the Neuroscience Graduate Program) was developing her own interdisciplinary course bringing together developmental biology and the sociology of gender.Sara’s course, which she is teaching this semester, is called “Intersex: Biology & Gender,” and is cross-listed in the departments of Biology, Sociology, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. “Intersex” is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with physical reproductive or sexual characteristics that cannot be easily classified as male or female (for more information, visit the Intersex Society of North America or the American Psychological Association’s page on intersex). FYI: October 26th was Intersex Awareness Day! In Sara’s course, she is teaching about both the developmental biology of intersex in humans and the social, political, legal and ethical issues related to intersex.

I wanted to interview Sara about her course because I see her work as highly relevant to the field of Neuroethics. First, Neuroethics benefits from interdisciplinary collaboration between scientists (especially neuroscientists) and researchers in the social sciences and the humanities, and by including material from the sciences, social sciences, and humanities, and by bringing together students from all of these fields, Sara’s course is fostering exactly the kind of interdisciplinary collaboration that Neuroethics needs. Second, Sara’s course is encouraging her students to grapple with important neuroethical and bioethical questions, including ethical issues related to the medical treatment of intersex individuals (see Dreger for a review) and ethical issues related to the use of intersex individuals as research subjects in scientific studies on sex/gender development. Read on to find out more about Sara’s course!

Question: What inspired you to teach the course?

Almost a year and a half ago, a friend of mine showed me a short documentary called “One in 2,000” which is about intersex in humans [for info about the film, visit this link]. I was surprised to learn how prevalent intersex is, and as a graduate student in the biomedical sciences, I was even more surprised to learn that the most common “treatments” for these conditions include surgical intervention to “normalize” ambiguous genitalia (often performed on newborns), gonad removal, and lifetimes of hormone therapy. I was even more outraged to learn that in the past, these procedures were oftentimes performed without full disclosure of medical information to the parents or to the patients themselves. Later in the video, as I watched dozens of names of intersex conditions drift across the screen, my outrage began to shift to embarrassment, because I only recognized four of them! Because my undergraduate and graduate training has been in reproductive biology, sexual behavior, and neuroscience, I expected that I would be fairly knowledgeable about the hormones, receptors, and developmental pathways that lead from an embryo through stages of sexual differentiation during development, and finally into a reproductively-capable and arousable adult man or woman. At that moment in time, my apparent intellectual ignorance of this topic, my outrage at the ethics of medical authority, and my growing interest in gender studies started to work together as a motivating force. I started doing some research and quickly learned that although many of the biological causes for intersex are well described, there remains a considerable lack of social awareness and understanding of intersexuality. With this in mind, I decided to draft a syllabus for an interdisciplinary undergraduate course about intersex in humans.

Question: When you originally designed the course, what did you want your students to learn from it? How did you plan to make the material accessible to students from the sciences, social sciences, and humanities?

I designed this class as a cross-disciplinary introduction to both the developmental biology and the sociology of intersex. It examines how biologically an intersexed body might develop and what the existence of these bodies means for the binary concept of gender in our society. I wanted to pose the question to my students, “What is a male and what is a female?” and to draw answers from a variety of disciplines. Thus, the course includes topics from the biomedical sciences, like chromosomal biology, embryology, endocrinology, and anatomy, as well as topics from sociology and the humanities, such as gender theory, the role of gender in our society, relevant legal, medical, and ethical issues, and what the study of intersexuality can glean from historical movements such as feminism.

It was very important to me that the course be cross-listed in departments from different areas of academia, and to my great delight, it was listed in the Biology department, the Sociology department, and the department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. I hoped that by studying medical ethics, the biology of human sexual development, and gender theory and sexuality, students from any academic background would appreciate the natural individual sexual variation in both human bodies and behaviors. Gaining these new perspectives relies on the unique level of discussion and engagement that results from a classroom of students from diverse disciplines who would otherwise not interact academically. For example, pre-med students from the Biology department would learn about the gender-related issues in the practice of medicine, which is a discipline that tends to uphold the binary approach to sex and gender. These pre-med students will undoubtedly have to make important decisions regarding sex and gender later in their careers as physicians, and it is critical for them to start discussing these concepts with students outside of their discipline. Similarly, non-biology majors from the Sociology or Women’s Studies departments would learn the specifics of the genetic, hormonal, and developmental basis of the human sexual variation that their disciplines have been studying and celebrating for decades.

At that point, as your question reflects, the challenge for me was to make sure that the material was accessible to the students. I hoped to accomplish this in a few different ways. First, I established an online, collaborative glossary and encouraged the students to keep track of each word in the course material that they’ve never seen before and to add those words to the collective glossary, along with a brief definition. I hoped that this exercise would attack the common and often reflexive feeling of stupidity that accompanies being exposed to a term or idea of which one was previously ignorant. In this way, as the students completed the reading assignments each week, they could celebrate and share the new words they learned. Right now, we have over 140 entries in the glossary, and almost all of my students are participating!

Second, I acknowledged that I cannot be an expert in every topic, and I invited several guest instructors from various departments to help teach the course. These incredible individuals include: Kara Kittelberger (Neuroscience), Jordan Kohn (Neuroscience), Kevin Watkins (Neuroscience), Katy Renfro (Psychology), Anson Koch-Rein (Institute of the Liberal Arts), Aimi Hamraie (Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies), Dr. Kim Wallen (professor in Psychology), Dr. Briana Patterson (pediatric endocrinologist from Emory Hospital), Dr. Pat Marstellar (director, Center for Science Education), and Dani Harris, an intersex person and advocate from the Atlanta community (Atlanta Police Department). During the planning and conceptualizing phases of my class, I also met with several other generous graduate students (Kristina Gupta, Cyd Cipolla, Mairead Sullivan, Pii Dominick), instructors (Dr. Kevin Cryderman, Dr. Sara McClintock, Dr. Deboleena Roy, Dr. Irene Browne, Dr. Tracy Scott), and staff members (Sasha Smith, Danielle Steele). Without these people, my class would not exist.

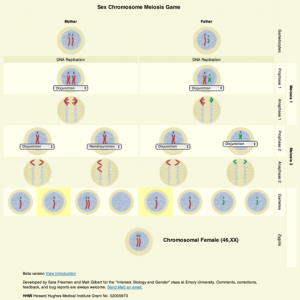

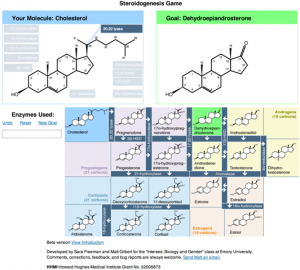

Lastly, in order to make two of the more challenging biological concepts accessible for all students, I collaborated with Matt Gilbert (web developer, graphic designer, instructor, and the friend who first showed me the “One in 2,000” documentary mentioned above!), to create two online, interactive “games”. The first is a meiosis game that allows students to interact with the X and Y chromosomes as they replicate and divide during the creation of eggs and sperm. Students can directly observe how variation in this process can result in an embryo with a set of sex chromosomes other than the expected XX or XY. The second online tool is a steroidogenesis game that outlines the complex enzymatic pathways that synthesize steroid hormones, such as testosterone and estrogen. Students can visualize how a body’s enzymes build these hormones and can interact with that process to test their knowledge. By making difficult biological pathways interactive, we improved the accessibility of these core biological concepts for all students.

The “meiosis game” Sara and Matt Gilbert created for the course

HHMI Howard Hughes Medical Institute Grant No. 52005873

The “steroidogenesis game” Sara and Matt Gilbert created for the course

HHMI Howard Hughes Medical Institute Grant No. 52005873

Question: How has the course been going so far? Have you been surprised by anything that has happened?

The course has been going wonderfully so far, in my opinion. The guest lecturers have been engaging, the students have been open and inquisitive during class discussion, and there has been tremendous support from the Emory community. As far as surprises, I think my own biggest personal surprise was that I haven’t really felt nervous. I was expecting to have to deal with some nerves each day before class, but I find myself comfortable in front of a classroom, which was definitely a pleasant surprise! I have also been pleasantly surprised at the great level of maturity that the students have exhibited in class. I imagined that because our discussion topics were often going involve details about the genitals and sexuality, it might be challenging for students to feel comfortable saying some of these words out loud. But they have been very mature and confident and have handled the course material better than I ever expected!

Question: Do you have any advice for other instructors who want to teach interdisciplinary courses?

Collaborate. Don’t be afraid to reach out to a distant department. Speak freely about your ideas. There are no dumb questions. Acknowledging the intellectual areas in which you feel weakest will likely result in a plethora of knowledge and support, which will overwhelm any potential inadequacies that may accompany that acknowledgement. It’s ok not to know the answer. Spend time following tangents. Be prepared to have the foundations of your knowledge shaken. Welcome alternative viewpoints. Learn to speak using unencumbered and discipline-free language, and if you find a situation where that is too difficult, be prepared to explain your word choice and its foundations to others.

Question: Has teaching this course influenced your current research in any way or your plans for future research? Has it influenced how you think about neuroscience research on sex and gender?

Yes, this course has definitely changed the way I think about neuroscience research about sex and gender. I’m much more critical of the field in general, and I’m also more aware of the misuse of the word “gender” to describe animals in a research study. Also, after learning so much about intersex subjectivity and medical ethics, I considered shifting my career track entirely! I felt compelled by the idea of studying the issues surrounding why many intersex individuals are lost to follow-up in the medical community, and I thought about applying for a post-doctoral position at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University. Instead, I decided to accept a post-doc offer to continue neuroscience research on peptide hormones and primate social behavior at UC-Davis next summer. While my research aims for the immediate future don’t include any specific plans to study intersex or gender, I definitely plan on teaching my intersex course in the future as often as I am able to.